It’s no surprise that the proliferation of technology has disrupted how companies do business. Organizations are at a threshold moment in their history, fighting to stay relevant in the face of increasing competition while looking to grow and enter the next stage of growth. They know technology plays a part in their future, but are unsure to what degree. For many organizations, becoming a technology company is the right approach. In many cases, it is the only approach for long-term survival. Though the lines are blurring for what constitutes a technology company, one thing is for sure: the new economy demands a cohesive technology strategy to remain competitive.

What follows is our take on the evolving nature of a tech company, why you might want to move further down the technology spectrum, and how your perception of technology impacts the strategic decisions you make as an organization.

A brief history of the technology company

As Ben Thompson covers in “What is a Tech Company,” the term was initially used when referring to computer hardware and software manufacturers. As the industry grew over time, what was once considered a computer became fractured, and we applied the label to an increasingly diverse set of companies. Software as a tool became integrated into more companies until those who simply leveraged software throughout their value chain gained the label as well.

This discourse around the definition of a technology company is not new. There have been countless articles written for both sides, and it’s often used as a heuristic when valuing startups. Those labelled as technology companies get far more generous multiples in their valuation.

In his seminal piece, Marc Andreessen introduces the power of software:

“Software is also eating much of the value chain of industries that are widely viewed as primarily existing in the physical world. In today’s cars, software runs the engines, controls safety features, entertains passengers, guides drivers to destinations and connects each car to mobile, satellite and GPS networks.”

By continuing along this path, we can see how any company starting to reconstruct its value chain to use software could become a tech company. As Alex Payne describes, it’s lost its value as a descriptor in many ways.

“It’s now accepted-going-on-cliché to say things like “software is eating the world”, which is an aggressive way of assuming that every company now has to be at least a bit of a technology company, and those that want to grow rapidly even more so. Many new companies targeting industries as diverse as eyeglasses and baby food are, at the outset, leveraging technology for everything they do: supply chain management, marketing, recruiting, internal communication, product development, and so on. This makes these businesses look like technology companies, if you squint. But, of course, they aren’t. They’re eyeglasses and baby food companies.”

What was previously used as a differentiator has become ubiquitous, much like the term “knowledge worker.” In the beginning, it helped distinguish the type of work into a category that allowed further analysis and insight into organizations. Once the entire landscape shifted and both knowledge work and technology were no longer rare, that unique lens proved less valuable.

As we reach the phase where every company is or should be using technology in some capacity, the label is becoming less helpful. It contains signalling value—“we are onboard with the software-eating future and will profit from it”—as well as embedded context. Even if it’s lost its meaning, we can still extract value from it.

The blurring lines of technology

Hardware and software products have proliferated in the consumer space, giving people unprecedented power in their everyday lives. From smartphones and tablets to connected conference rooms and employee intranets, this familiarity and comfort with technology has had cascading effects on the workplace. Whether we embrace it or not, many of us are now the self-contained IT departments of 2003. We are comfortable finding digital tools to help our work, rely on our computers to get work done and have a basic understanding of troubleshooting. This is true not only in the workplace but in our personal lives, too—69% of U.S. online adults shop more with retailers that offer consistent customer service both online and offline. Additionally, almost three-quarters of Americans are using digital channels, both online and mobile, to conduct their banking.

But it’s not just about using software to create an advantage. Andreessen outlines how some traditional businesses have evolved to adopt the technology company label:

“Today’s leading real-world retailer, Wal-Mart, uses software to power its logistics and distribution capabilities, which it has used to crush its competition. Likewise for FedEx, which is best thought of as a software network that happens to have trucks, planes and distribution hubs attached. And the success or failure of airlines today and in the future hinges on their ability to price tickets and optimize routes and yields correctly — with software.”

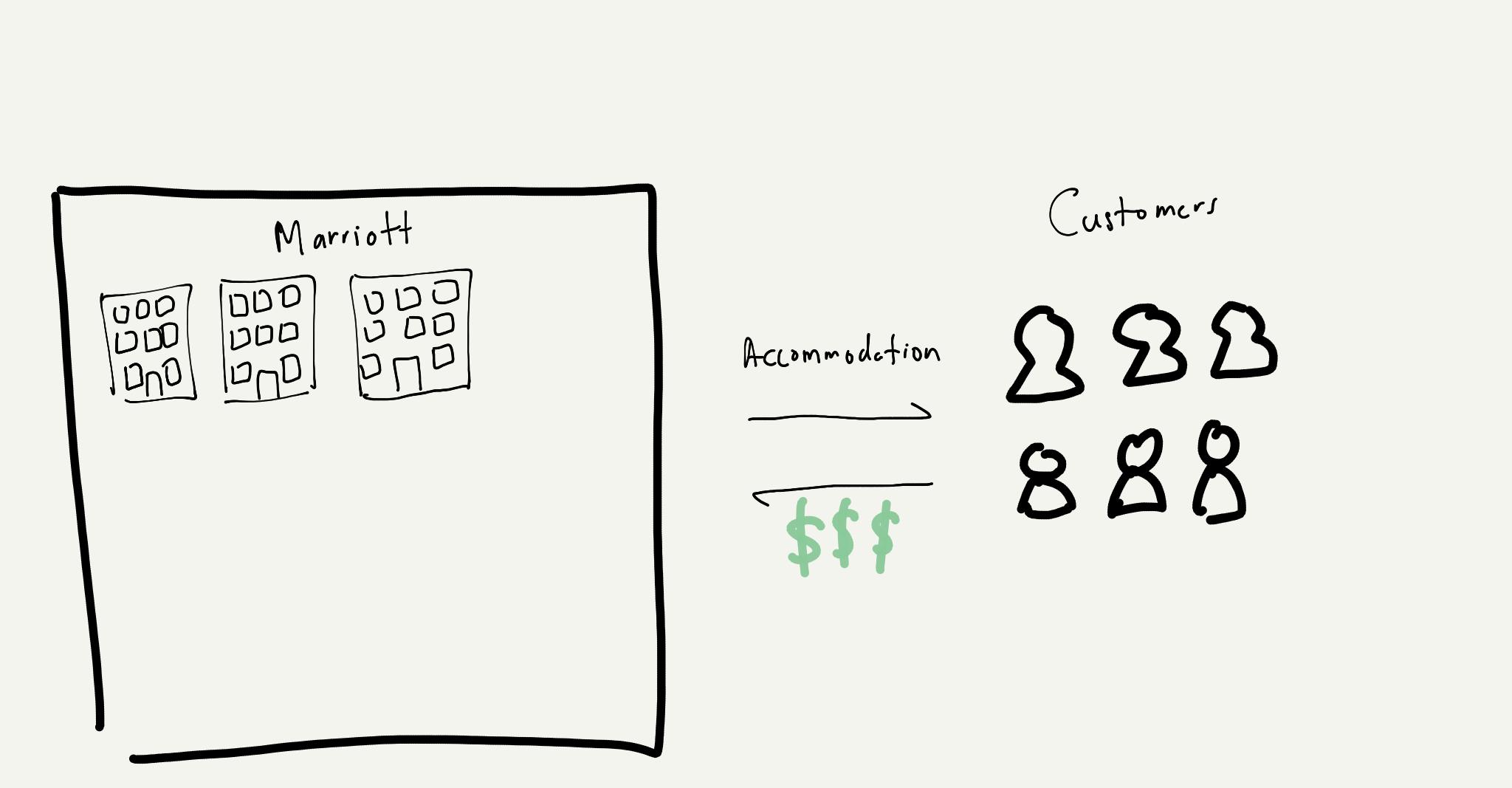

Marriott

Marriott is one of the largest hospitality groups, consisting of hotels and lodging across the world. They make their money by owning and operating hotels, providing accommodation for millions of people each year. They own around 30 different brands and manage over 1.3 million rooms. They have been in business for 92 years and are unequivocally not a tech company—they solely operate in the physical world. Marriott buys and leases real estate and rents it out to customers. They employ housekeeping staff, concierge services, chefs, and more. Their tangible assets consist primarily of cash, accounts receivable, and the real estate they own. When customers are looking for accommodation, they count on companies Marriott to provide a space to stay.

When a customer buys from Marriott, often when travelling, they are getting a place for their family to stay. They seek security, shelter, and a pleasant experience.

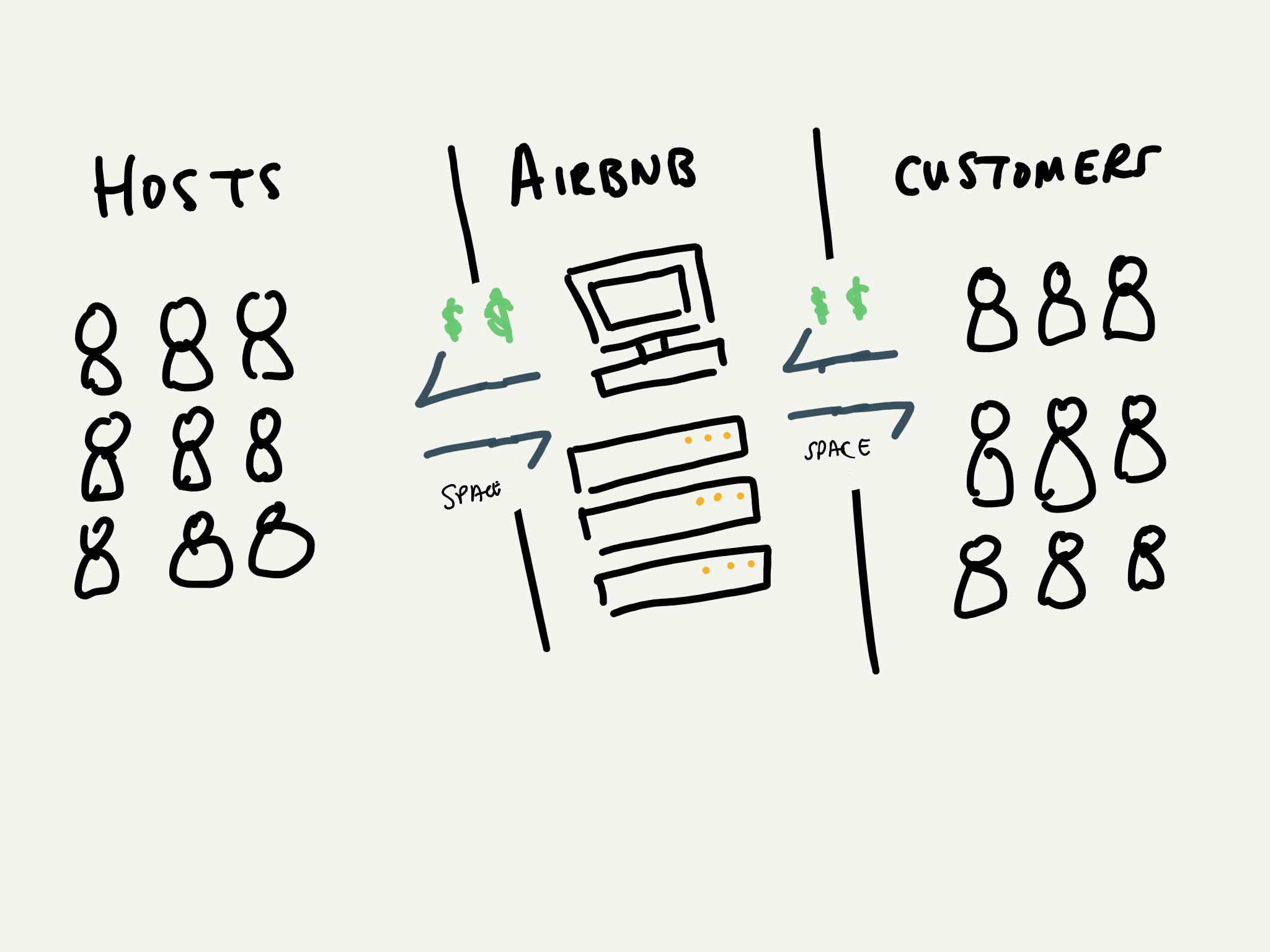

Airbnb

Now, let’s take a look at a modern competitor in Airbnb. Airbnb is a digital platform for both managing and booking lodging. Instead of directly owning properties, Airbnb depends on supply provided hosts and matches it to demand from different customer groups. Hosts with extra property or space available in their current lodging can sublet it through Airbnb, much like the consignment model in retail. They post their inventory onto the platform and wait for a customer seeking accommodation to reach out. Airbnb is the service in the middle, facilitating the transaction. Airbnb is a technology company, but not a software company (defined as a company selling software), as their end-product is simply facilitated transactions. They are a modern marketplace.

You can argue Airbnb is a service company, not a product, but Airbnb doesn’t employ traditional hospitality staff. Their team is your standard makeup of technology workers (designers, engineers) and customer service. From a financial standpoint, Airbnb assets likely consist solely of cash and investments (they are private as of writing this, so I can’t confirm). As a technology company, their most valuable pieces are their people and their technology. What difference does this make?

Marriott versus Airbnb

If you’re a customer looking for a place to stay while travelling, you can go to either Marriott or Airbnb to find the accommodation you need. These two companies provide the same good in the minds of many consumers. You can just as easily substitute “hotel” into the sentence “my Airbnb stay was great.”

So why is one a technology platform and another a hospitality company?

If you care about building an enduring, customer-focused company, your inner classification is not important.

Instead of looking for an explanation, which is not too complicated, I’m going to throw you a curveball: it doesn’t matter. If you care about building an enduring, customer-focused company, your inner classification is not essential. In the customer’s mind, both companies provide lodging and appear as comparable products. Have you ever asked someone to just think about what Airbnb is? Try asking a friend or family member. For many, Airbnb is a website. Or it’s an app. Or it is a digital product: something you use when looking for accommodation. Airbnb is a tool you use to search for potential destinations, communicate with your hosts, and manage your upcoming trips.

This may be a symptom of having a namesake product, but also a helpful heuristic for evaluating a tech company. How can these two companies be so similar yet so different in a customer’s mind?

Let’s revisit Marriott with this perspective.

- Does Marriott have an app to book, communicate, manage your travel? Yes.

- Do they have a website for you to browse their offerings? Yes.

- Do they use digital tools internally to manage their guest experience? Yes.

From this perspective, Marriott is starting to look a lot like a technology company from the outside. Is the sole distinction in this case who owns the inventory? In a way, yes. But we can start to see how narrow this line truly is and begin to find ways to tip-toe over to the other side. Technology companies often lead the way for setting customer expectations, building the next generation of consumer products. For many customers, this focus on experience is enough to warrant a switch to the newcomer instead of sticking with the incumbent.

Attempting a transition

When looking at traditional companies like Marriott versus native-technology companies such as Airbnb, it’s easy to think the only way to be a tech company is to start as one. Like all companies, tech companies still start small, often with a niche, before slowly growing into the competitive forces they are today. This puts larger organizations on a reasonably fair, if not advantageous, playing field. They have a larger ship to turn in a new direction, but they have the power of existing revenue, relationships, and experience to propel them faster.

Whether your company is a technology company by formal definition or not, it’s helpful to think of yourself as one and start to make decisions accordingly. Strategically investing in technology as one of your core products, you can begin to compete with tech companies in the long run. If you succeed in making technology a priority, you might start to build momentum, keeping you relevant and hopefully competitive in this changing world.

In Part 2 of our series, we will explore how to build a tech company from the ground up.